|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Current Educational Trends in Library and Information Science Curricula

Karen M. Drabenstott

Abstract

To set the stage for identifying current educational trends in library and information science (LIS) curricula, the author reviews the impact of the striking and tumultuous technological changes that have occurred in the last decade and speculates on how these changes will affect our field in the not-so-distant future. She encourages LIS faculty to speculate on the future to prepare themselves for making changes to their curricula that complement change and future developments. The author describes findings of a survey of information published on the Web sites of North American schools of library and information science. The objective of the survey was to determine new trends in educational practices in the form of new courses, course concentrations, and programs. It comes as no surprise that LIS schools are pursuing new opportunities that are technology- or systems-centered. LIS faculty are encouraged to examine the new content areas that North American LIS schools are now offering and embark on new opportunities that make sense in view of their view of the future, expertise now on staff, available resources, and the resources they are able to secure to make changes at their institutions.

Speculating on Change and New Technologies

New Technologies

The most obvious change has been the tremendous growth in technology. Especially since 1993, the emergence of the World-Wide Web has fostered the migration of traditional information packages such as books, magazines, newsletters, and newspapers to digitally-encoded forms which people can display and manipulate in new ways that were never possible with their analog counterparts. The World-Wide Web has made it possible for information to be available at anytime and anyplace-24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and 365 days a year, or "24/7/365." Furthermore, information can be tailored to individual needs, desires, and preferences. For example, a new service that Web portals and other Web-based information providers now provide enables everyday people to formulate and submit profiles of their interests to these services, retrieve news and information that pertain to their interests, display and download retrievals, and send retrievals in electronic mail messages to colleagues and co-workers.

Entirely New Forms of Communication

New technological developments have spawned entirely new forms of communication that rely on technology and have no counterpart in traditional print forms of communication. Certainly, we are now familiar with web-based newspapers and magazines. Right now, these forms have many similarities to their print counterparts but they also have features that their print counterparts did not have such as colored photographs, video files, search engines, updated sports scores, and personalized news. What I foresee in the not-so-distant future are new forms of communication that only technology can make possible. These new forms will be a convergence of media, virtual reality, and recorded knowledge. Technology will make it possible for us to transform our thoughts and creations into new forms of expression that mirror ourselves more completely, and, eventually, exceed ourselves. Increasingly technology will become more transparent and future forms of communication will not burden people with problems of use and usage that make today's inventions so difficult for everyday people to use and to adapt to.

Impact on Authorship

In the future, authorship will become much more than just words on paper. Future "documents" will be a synthesis of media, virtual reality, and recorded knowledge. They will require continual revision and permissions and royalties for use of recorded media. No longer will one or two people be responsible for the production of future "documents" or will we be able to attribute their production to one or two individuals. Instead, authors will be supporting members of rather large production teams and such teams will resemble the production teams that produce today's films and television programs. Production of many future "documents" will be long-term events because the information in these documents will require constant revision and updating.

Content Publishers

In the near future, content publishers will undergo a transformation to support the changes in authorship from lone individuals who work in solitude using their own resources to production teams that operate like the film and television industries in their support of live and videotaped programming. Such teams will be necessary to capture phenomena in digital forms and transform what we now convey using verbal expression into entirely new visual expressions and experience. The transformation that is destined for content publishers will neither be instantaneous nor inexpensive. It will probably require a combination of the computer, publishing, and entertainment industries. And the "documents" that emerge from such a combination aren't going to be freely distributed on the World-Wide Web or future iterations of that medium. Such documents will require payments in the form of subscriptions, standing orders, or, in fact, entirely new economic models to sustain them over the long periods of time that will be needed to support the full term of their expression.

Database Publishers

Changes in authorship and publishing force us to reexamine the role of database publishers. Today, the vast majority of these publishing intermediaries gather and index published and unpublished written material that is similar in subject, form, or combinations of the two and formulate surrogates that express the intellectual contents of this material. We can even consider Web search engines, e.g., Alta Vista, Excite, Google search, Hotbot Lycos, Northern Light Search, and web browsing directories, e.g., Argus Clearinghouse, Canadian Subject Guide, Google Web directory, Magellan, Yahoo, to be a type of database publisher because they gather and index written material that is published on the World-Wide Web, that is, material that is similar in form.

Will there be a need for database publishers in the not-so-distant future? Or will their role be assumed by content publishers who formulate sophisticated previews that summarize content using both verbal and visual expressions and publish previews without copyright or use restrictions to publicize compelling content? Or will their role be assumed by intelligent agents, that is, smart computer programs that people profile themselves and dispatch across the network to find material that interests them?

Users (that is, Everyday People)

Let's factor users into the equation. Today, users (or everyday people) purchase information through subscriptions to book, audio, and video clubs, through membership fees to professional associations, and through one-time purchases at bookstores. They purchase and consume the inexpensive information made available through newspapers and magazines. They photocopy, read, or borrow holdings from libraries. They surf the World-Wide Web and find information through searches of web search engines and browsing services, suggestions from friends or colleagues, or just plain luck and serendipity. They get advice from family, friends, and colleagues and sometimes borrow material from their personal collections. Of course, people who are employed in important and powerful positions in business, government, and industry, enlist the resources of their employer to secure the information that assists them in decision making. But, for the most part, everyday people don't invest a lot of their own money in the information that they need to lead useful and productive lives.

This is about to change. Information in the not-so-distant future won't be free. Network-based information will be costly to create and produce. And, because much of this information will be both entertaining and compelling to consume and experience, people will want access to it.

Libraries Today

This brings us to the role of libraries. Today libraries are sources for physical collections of traditional information packages such as books, journals and magazines, newspapers, pictures, and audio CD-ROMs. People borrow, read, listen to, view, and/or photocopy library materials. Only one person at a time can use traditional library material because of the limitations imposed by its physical format. Libraries have begun to build digital collections and strike licensing agreements with information providers and distributors to allow multiple uses of digital databases, reference sources, journals and magazines, picture files, newspapers, and so on. Some licensing agreements are rather restrictive and allow one use per "purchased" or "leased" resource; for example, netLibrary requires its licensees to purchase multiple copies of electronic books to enable multiple uses of these e-books. Other licensing agreements are less restrictive and allow libraries to specify the maximum number of simultaneous uses or users. One of the most important technological advantages to digital collections is simultaneous usage of digitized artifacts but the number of users that can use a particular resource is tied to licensing, not to technology.

Libraries in the Not-so-distant Future

In the not-so-distant future, it is entirely possible that publishers, distributors, and other intermediaries may opt to bypass libraries altogether and market their artifacts directly to everyday people. Can people afford to purchase digital information? If large numbers of people bypass libraries and purchase digital information, will their purchases be sufficient to support the future publishing industry? Will we see information providers emerge that resemble the cable industry, that is, they connect people to large numbers of "channels" of digital information that vary in subject, form, genre, ideology, etc.? The author really doesn't know the answer to this question but she concludes that it is entirely likely that future information providers will make a significant effort to market their artifacts directly to everyday people and the result could be an even wider gulf between the "information-haves" and "information-have-nots" than exists today.

Being optimistic, I believe future information providers will view libraries as efficient intermediaries in the information distribution process, That is, information providers will continue to serve libraries because they know that it is through libraries that they can reach everyday people who will consult the resources they license to libraries. However, information providers will require libraries to pay for digital information and simultaneous uses of it. And the arrangements that such providers make with libraries will vary-these will be licensing, simultaneous uses, one user per copy, pay-per-view, and other arrangements that are yet to be determined. Both information providers and libraries may resort to advertising to raise people's consciousness about the availability of certain resources and to educate them about the benefits of these resources. And, eventually, libraries will demand remuneration or rebates from information providers based on estimated and actual use of information resources.

To summarize, the author believes that libraries will continue to subsidize the public's consumption of information and she is not alone in this regard (Miksa 1996). People will continue to rely on libraries because they cannot afford to purchase information on a large scale, and, in view of the expense of future information packages which will require large production costs, they certainly will not be able to afford huge increases in the cost of information.

Of course, there is the problem of preserving future digital forms of information. Preservation is such a difficult problem that all this paper can do is to acknowledge the problem and suggest that future contributors to CASLIN examine near-, medium-, and long-term solutions.

Technology-driven Change

Someday soon, we might look upon the Internet, Gopher, and the World-Wide Web as the last great "golden era" of "free" information. Some prognosticators are so bold as to predict that technology will soon replace paper (Olsen 2000). The author believes that digital information will someday replace paper but not entirely. Here are several important reasons why paper will survive for sometime to come:

- Technologists have yet to create electronic devices that are as convenient and versatile as paper.

- The base of "authors" who have the ability to express themselves both verbally, visually, and aurally in new digital forms is yet to be developed.

- Publishers must undergo a transformation to support authors and the production teams needed to represent their creations in new digital forms, especially forms that require continual revision.

- New forms of communication must be so compelling and desirable to people that they no longer want traditional print-on-paper communications.

- New economic models that make new forms of communications accessible to people have yet to be invented.

For now, technology gives us more choices in the ways in which we express ourselves and communicate with other people. Eventually, the desires of everyday people for media-rich productions will usher in new forms of communication that are a convergence of media, virtual reality, and recorded knowledge and people won't want information on paper. The problem is that compelling new forms of communication won't be inexpensive to produce and maintain and someone, probably the people who and institutions (like libraries) that want to access these new forms, will have to share the cost of their production and distribution and ensure a profit for their creators.

Examining Trends at North American LIS Schools

Method

The author surveyed the Web sites of North American schools, departments, and colleges of library and information science (LIS). The objective of the survey was to determine new trends in educational practices in the form of new courses, course concentrations, and programs. In March 1999, she consulted the list of 52 schools maintained by Elizabeth Lane Lawley. When she visited the Web site of each institution, she collected the following information:

- Professional degrees offered by the school, department, or college;

- Affiliated schools, departments, and colleges;

- Joint (or dual) degrees;

- Core courses;

- Electives, programs, and course concentrations.

Not all 52 schools, departments, or colleges provided the desired information for each of the five areas and sometimes this information had to be extrapolated from the information provided on the Web site. Based on the analysis of collected data, the author suggests new content areas that LIS schools ought to consider in terms of new courses, course concentrations, or new programs.

Names of LIS Schools

Figure 1 is a bar chart summarizing the number of schools with various names. Twenty-three institutions are named School (or Department or College) of Library and Information Science(s). The number of similarly-named schools drops dramatically to six for School (or Department or College) of Library and Information Studies and five for School (or Department or College) of Information Studies.

Figure 1. Names of LIS schools

Key to figure 1:

LISc = Library and Information Science(s)

LISt = Library and Information Studies

IST = Information Studies

ILSt = Information and Library Studies

LISr = Library and Information Services

Fourteen schools had unique names. Most of these unique names included phrases such as "library and information science(s)," "information and library science(s)," and "library and information studies." But they also included the following unique terms and phrases:

- Archival studies;

- Communication;

- Instructional Technology;

- Information Management;

- Information Resources;

- Information Systems;

- Librarianship;

- Media Studies;

- Policy.

Professional Degrees

Generally, LIS schools (or departments or colleges) award masters degrees in library and information science. Although the wording of these degrees varies considerably, most degrees contain the words "library," "information," and "studies" or science(s)," e.g., masters of library science (MLS), masters of library and information science (MLIS), masters of information and library science (MILS). Some schools award masters degrees that have rather different names. Some of the most unique masters degrees included the following terminology or were masters of science (MS) degrees in the following specializations:

- Book arts;

- Communication;

- Economics and policy;

- Human-computer interaction;

- Information resources management;

- Information science;

- Instructional technology;

- Journalism;

- Software engineering;

- Telecommunications and network management;

- Virtual reality.

In addition, core and elective courses connected with masters degrees in the above specializations were almost always different from the courses in which students enrolled to obtain degrees in library and information science. However, some schools were quite liberal about course requirements for students who sought library science degrees and the other degrees listed above.

Joint (or Dual) Degrees

The majority of schools offered joint-degree programs that focused on subject mastery. Most graduates of such programs would seek positions in academic or special libraries and become specialists in a particular subject. Examples are area studies (e.g., Asian studies, American studies, Pacific Island studies, Latin American studies), art, business, law, music, religion, and science. Other joint degrees led graduates to seek professional work in library-related settings. Examples are listed below along with the department in which students pursued joint degrees.

- Archives (joint degree with history or materials studies).

- Antiquarian bookselling (joint degree with English or Classics).

- Geographic information systems (joint degree with Geography).

- Information policy (joint degree with public policy, politics and government, or political science).

- Management information systems (joint degree with business).

- Medical informatics (joint degree with medicine).

- Systems (joint degree with computer science).

Core (or Required) Courses

Of the 52 schools surveyed, 46 schools identified core (or required) courses on their Web site. Since the names of core courses varied, I studied the descriptions of core courses and categorized them according to content. In some cases, courses spanned two categories. And some schools required more than one core course in one area. Figure 2 summarizes core courses at 46 schools.

Figure 2. Core courses

Key to figure 2:

Org. = Organization of information resources (including cataloging)

Fndns. = Foundations of the LIS field

Ref. = Reference services and sources

Mgt. = Library management

Research = Research methods

Tech. = Technology

IR = Information retrieval

Users = User needs and behavior

Coll. dvt. = Collection development

Although not all 46 ILS schools that identified core courses required students to take courses in the "organization of information" area, there was a large number of core courses categorized into the "organization of information" area-48 courses to be precise. There were 46 courses categorized into the "foundations" category. Not all 46 schools required "foundations" courses so there were a few schools that required more than two "foundations" courses from their students. Overall, twenty or more core courses were categorized into one of six areas:

- Organization of information;

- Foundations of LIS;

- Reference services and sources;

- Library management;

- Research methods;

- Technology.

Core and Elective Courses

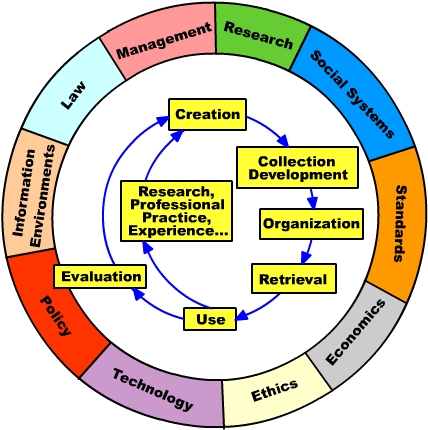

To categorize both core and elective courses, the author turned to the lifecycle of information, a visual representation of information that summarizes the phases through which information passes from creation to disposition. The inner circle of figure 3 depicts the lifecycle of information. The lifecycle begins with the "creation" phase in which authors, composers, artists, and other creative or productive individuals and organizations create information. Libraries then collect information ("collection development" phase), organize it ("organization" phase), and submit information to manual and online systems for retrieval ("retrieval" phase) by intermediaries or end users ("use" phase). There are also phases for "evaluation" and "research, professional practice, and experience" in which consumers of information put new knowledge to work in the creation of new inventions, new ways of thinking and doing things, and, ultimately, in the creation of new information ("creation" phase again).

Figure 3. Core courses, elective courses, and the lifecycle of information

Generally, LIS schools offer core courses and elective courses that are described by the lifecycle of information; however, encircling the lifecycle of information is a second circle that cites important factors in terms of fields, disciplines, and tools that affect the lifecycle of information (figure 3). For example, economics describes a field on which information professionals and providers rely to price and distribute information and support the creation of new information.

Figure 3 is complex because it summarizes the course offerings of LIS on a high level. In the following subsection, each phase in the lifecycle of information is discussed in more depth.

Lifecycle of Information and LIS curricula

Until the birth of the World-Wide Web in the early 1990s, "creation" was very much underrepresented in terms of course offerings in LIS schools. Schools offered courses in "Publishing," "Audiovisual materials," and "Storytelling" but they really didn't offer courses in which students created content from scratch. Now "creation" courses are much more common in LIS curricula. Examples are the courses:

- CD-ROM publishing;

- Electronic texts;

- Graphic design;

- Information graphics;

- Instructional design;

- Multimedia production;

- Oral history;

- Technical writing;

- Videotape production;

- Web site design and production.

Collection development has been a staple of LIS curricula for many years. Now the one or two courses in collection development that LIS schools typically offer go beyond print collections to include network-based collections.

The "organization of information" phase is one of the most well-represented areas in LIS curricula. Today's courses go beyond the organization of print materials using well-known cataloging standards such AACR and MARC and include organization of network-based resources, development of controlled vocabularies, establishing standards and crosswalks between standards. Students are also introduced to new approaches to organizing information with entirely new acronyms and objectives, e.g., HTML, SGML, XML, RDF, Dublin Core, EAD.

The "retrieval" phase is also one of the most well-represented areas in LIS curricula. Emphasis on traditional collections and online databases has given way to a new emphasis on network-based information and systems. We are training students how to assist end users to find information in an increasingly heterogeneous information environment that consists of traditional, print-based sources, network-based sources of information, and a few connections between the two. We are preparing students for positions in which they will train end users "to access and evaluate information effectively for problem solving and decisions making" and to become "lifelong learners in an information society" (Tiefel 1995, 326).

Courses categorized in the "use" phase often focus on certain types of users such as children, young adults, scholars, new immigrants, ethnic minorities, disabled, and aged. Faculty are adding content to courses in the "use" phase that takes into consideration user needs and behavior, especially the strategies that model how people search for information.

"Evaluation" courses address this lifecycle phase from two perspectives: (1) evaluation of information systems or information services, and (2) research methods for conducting evaluations of such systems or services.

One possible output of information consumption is the creation of new knowledge, and, like the "creation" area, LIS schools offer few, if any, courses in this area. The catch-all phase entitled "Research, professional practice, and experience" includes courses in research methods in which students learn quantitative and qualitative research methods so they can undertake research projects and add to the knowledge base of library and information science. With regard to professional practice and experience, some schools offer internships and summer placement opportunities in libraries and other information-intensive organizations so that students gain on-the-job training and experience to complement what they learn in classrooms.

Important Factors Affecting the Lifecycle of Information

Of the ten factors affecting the lifecycle of information, LIS schools have been especially active in featuring courses in the "information environments," "management," and "technology" factors. Table 1 enumerates the many classes that LIS schools offer per factor.

Table 1. LIS Courses and Important Factors Affecting the Lifecycle of Information

| Information Environments | Management | Technology |

| Academic libraries | Accounting | Artificial intelligence |

| Cultural heritage institutions, e.g., museums, schools, historical societies | Decision-making | Computer literacy |

| Digital libraries | Entrepreneurship | Cryptology |

| Government agencies | Finance | Data and file structures |

| Nonprofit organizations | Forecasting | Data mining |

| Prison libraries | Human resources | Data fusion |

| Public libraries | Leadership | Distributed computing |

| Special libraries | Marketing | Library automation |

| Organizational behavior | Networking | |

| Policy formulation | Privacy | |

| Promotion | Programming | |

| Software lifecycle management | ||

| System design, development, deployment, and evaluation | ||

| Telecommunications |

No one school can cover every aspect of the lifecycle of information in depth due to limited resources. Schools instead specialize and offer new programs or concentrations that are described by one of the factors surrounding the lifecycle of information in figure 3. These specializations could be categorized into the lifecycle of information, but they are especially important because they describe entirely unique opportunities that have come about due to new developments in information technology and networking. Some specializations, e.g., archives, information science, and cognitive studies, are familiar because they are relevant to the handling of print-based materials in information-intensive organizations and schools have offered them for a long time. In recent years, faculty have made significant changes to these specializations to reflect the impact of information technology and networking. For example, archives has long been a specialization that some LIS schools have offered but the importance of archival methods and techniques has grown due to the problems of preserving digitally-encoded data. LIS schools have responded to the challenge and have made significant changes to curricula to reflect the importance of preservation and digital data.

Table 2 lists 15 new content areas that LIS schools are addressing through the establishment of new courses, course concentrations, or entirely new degree programs. "Information design," one of the 15 areas listed in Table 2, is not offered at any LIS school but some schools have considered expanding their curriculum to include content in this area.

Table 2. New Content Areas for the LIS Curriculum

| New content | No. of Schools | Brief description |

| Archives | 27 | Preserving knowledge especially digitally-encoded data |

| Competitive (or strategic) intelligence | 8 | Information service at corporations that supports decision-making through processed or hidden information |

| Human-computer interaction | 8 | Building user-centered interfaces for network-based information systems |

| Natural language processing | 5 | Building systems that respond to the people's language, not a meta-language |

| Information science | 4 | Building responsive information retrieval systems, question-and-answer systems, improving relevance feedback, data mining, data fusion... |

| Expert systems | 4 | Building systems that make recommendations based on expert knowledge |

| Community information systems | 3 | Building information systems that serve communities, civil society, and the not-for-profit sector |

| Computer-supported collaborative work | 2 | Designing new organizations and the technologies of voice, data, and video communication that make them possible |

| Information visualization | 2 | Building interactive graphical interfaces to reveal structure, extract meaning, and navigate large and complex information worlds |

| Electronic commerce | 2 | Determining the cost and value of creating information and delivering electronic information |

| Information architecture | 2 | Organizing information and designing information packages such as Web sites, corporate intranets, to access it |

| Cognitive studies | 2 | Understanding how people think, organize, learn, and solve problems |

| Mass communications | 1 | Understanding how new information technologies have converged with conventional media to form new forms and new opportunities |

| Cyberspace law | 1 | Legal issues in information management such as antitrust, contract management, privacy, libel, constitutional rights, international law including intellectual property, transborder data flow |

| Information design | 0 | Designing easy-to-use, self-instructional information packages |

Expanding the Curriculum in LIS Schools

Expanding the curriculum in LIS schools is not an easy task. There are as many ways to move forward as there are schools that have introduced change to their curriculum. The author's experience with changing the curriculum at the School of Information at the University of Michigan has demonstrated that faculty are the key to making change.

To get started, faculty could speculate about the future by reading relevant material in the literature. Don't just study LIS literature-consult the published literature about future developments and impacts from related fields and disciplines. Faculty should share their discoveries with their colleagues and, together, arrive at consensus, truths, or consequences about how the future will affect the field and the school. They could also expand their discussion to include faculty from schools, departments, and colleges at their own institution who work in related fields. Eventually faculty need to decide areas that need substantial improvement and areas that are important to add to the curriculum.

To support change in the curriculum, faculty may have to seek new staff to teach in new areas. New faculty appointments are costly. Some schools have made joint appointments with senior faculty in related schools or they have found "creative" approaches to adding to the faculty. For example, they have invited professionals from the community to offer courses in new areas. In North American, such positions are called "adjunct" faculty. The University of Michigan allows schools to make "clinical" faculty appointments. Clinical faculty are hired on contract for two to five years and attend to teaching and service obligations. (Regular, tenure-track faculty also have a research obligation.) Schools typically award clinical faculty appointments to working professionals who bring their cutting-edge skills and knowledge from their jobs to the classroom.

Undoubtedly the most "painful" approach to making changes in the faculty is to retrain faculty. This approach is "painful" because schools rely on such faculty to sustain existing programs while they engage in retraining. Administrators should relieve such faculty of the research obligation while they seek retraining. Furthermore, the retraining process may not be straightforward; faculty may be unsure how to proceed in learning about fast-developing areas and follow paths that fail to bear fruit in the course of their retraining program.

Adding new programs may necessitate additional resources to support new faculty, hire support staff, add space, and acquire equipment, software, supplies, accounts, etc. Financial support for making changes to an academic program always requires administrative support at middle and high levels. In North America, some schools have sought support through grants to foundations and government agencies. If faculty and administrators are unable to secure financial support from their own institution, they may be forced to reduce or terminate outdated programs or programs that duplicate another organization's strengths to move forward on their own plans for change. This approach is perhaps the most "painful" way to introduce change but, in the absence of financial support, it may be the only way to introduce change.

Faculty should also consider offering joint degrees with related schools, departments, and collages. In the School of Information at the University of Michigan, we have established joint degrees with Business, Law, and Public Policy ("Dual degree programs" 1999). To fulfill the requirements of both programs, students in joint-degree programs are required to enroll in the core courses of the two programs and to enroll in the elective courses of the two programs but they do not have to take as many elective courses as students who are enrolled in only one program. So, students in joint programs usually complete course requirements in three years instead of four years. In addition, the University of Michigan has relaxed rules about joint programs and allows students to propose their own joint programs to the schools that interest them and obtain approval from these schools to embark on their own course of study.

Another approach to adding new faculty and programs is to merge with related schools. In North America, LIS schools have merged with related schools to form larger, more comprehensive units. Such schools now include faculty in communication, education, instructional technology, and policy.

Summary

The impact of new technological developments on authors, content publishers, database publishers, and library users is reshaping the ways in which libraries do business. While this paper speculates on the nature of that impact, it is important for librarians to engage in such an exercise to arrive at their own ideas about where the field is headed in light of new technologies.

To identify current educational trends in LIS curricula, this paper describes the findings of a survey of information published on the Web sites of North American library schools. This information involves the names of schools, the professional degrees they awarded to graduates, joint degrees, core and elective courses. The objective of the survey is to determine new trends in educational practice in the form of new courses, course concentrations, and programs.

It comes as no surprise that new educational trends are technology- or systems-centered. However, some schools continue to offer specializations that they have offered in the past, e.g., archives, information science, and cognitive studies, and have made significant changes to these specializations to reflect the impact of information technology and networking. For example, archives has long been a specialization that some LIS schools have offered but the importance of archival methods and techniques has grown due to the problems of preserving digitally-encoded records and files. LIS schools have responded to the challenge and have made significant changes to curricula to reflect the importance of preservation and digital data.

Table 2 lists new content areas that are now represented in LIS curricula. While no school has the resources to include all content areas, schools need to examine existing resources, speculate on how they expect new technologies to impact the field, and embark on new opportunities that make sense in view of expertise now on staff, available resources, and the resources they are able to secure to make changes at their institutions.

References

[1] "Dual degree programs at SI."(1999 August 2). http://www.si.umich.edu/academics/dual/. (November 12, 2000).

[2] Drabenstott, Karen M., and Daniel E. Atkins. (1996). "The Kellogg CRISTAL-ED Project: creating a model program to support libraries in the digital age." In Advances in Librarianship, edited by Irene P. Godden, 47-68. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press.

[3] Lawley, Elizabeth Lane. (1996). "LIS schools on the Internet." http://www.itcs.com/topten/libschools.html (November 12, 2000).

[4] Miksa, Francis. (1996 January 16). "The cultural legacy of the 'modern library' for the future." http://www.gslis.utexas.edu/~miksa/modlib.html (November 12, 2000).

[5] Olsen, Florence. (2000 August 18). "Logging in with William Arms: 'open access' is the wave of the information future, scholar says." Chronicle of Higher Education 46, 50.

[6] Tiefel, Virginia. 1995. "Library user education: examining its past, projecting its future." Library Trends 44, 2 (Fall): 318-338.